You're Not Ugly, You Just Need To Travel

on desirability, and being dark-skinned in California vs London

This essay is based on a YouTube video I made last year. Check it out if you are interested in watching rather than reading!

In 2011, I took the trip that changed me.

I was 19, studying abroad in London, and for the first time in my life, I felt seen. That experience shaped so much of who I am today—it sparked my love for travel, my courage to do unconventional things, explore the world solo, and my passion for encouraging Black women to be carefree and explore the world. Everything I’ve done since then, every major pivot in my life, in some way, anchors back to that trip.

I grew up in California in the ‘90s and early 2000s . I'm a California girl. Shout out to Katy Perry. And if you know, you know—there was always this unspoken currency placed on being light-skinned, mixed, or biracial compared to being dark-skinned and African. This may have been true in other parts of the U.S. as well, but I can only speak for California. Listen, being a dark-skinned African girl back then? We were fighting for our lives.

The bullying, the insults, the classroom lights going off and suddenly everyone’s facetiously asking, “Where did Anayo go?” —it was wild. As a sidenote, it’s crazy to see how Afrobeats and Nigerian culture are so widely celebrated now because I remember when being African was absolutely not it. And being African and dark-skinned? Chile.

I learned to retreat inward. I was shy, docile, and quiet—the eldest daughter of immigrant parents who were too busy surviving in a new country to be able to understand what their daughter was going through in a world that barely acknowledged her.

Attention? Never had it. Being chose? Don’t know her. The girl people thought was pretty? Not me. I was a tomboy and felt really comfortable in that. I leaned into it, and looking back, I think it was a form of protection. Tomboys weren’t expected to be feminine or attractive. Tomboys don't get looked at. Tomboys are the homie. Tomboys fly under the radar. And I liked flying under the radar. Flying under the radar meant nobody was teasing you, and nobody was saying your name wrong. It meant I wasn’t the target of another cruel joke about my culture or my name. I was just, “That's that person over there.” Cool. I'll take that over being called an African booty scratcher.

I played that role so well that by the time I got to college, that's the role I quietly slipped into. I quietly slipped into my classes, quietly slipped into the dining hall—I was just there. I went to a PWI, and at that point I was entirely removed from the world of liking men and having crushes. I had already trained myself not to expect attention, so I faced my books, as Nigerian parents would say. I was there to get my degree, not to entertain the possibility of being desired.

But at the same time, there was a small part of me that was yearning for attention. Not to be the center of it, but to be seen.

I applied for a study abroad program during my junior year. Back then, it was unheard of, and frankly, weird, for a young Nigerian girl to go do this. But I was studying Italian and obsessed with Italian culture at the time. I convinced myself that one day I was going to live in Italy and live la bella vita and just eat gelato and drink wine all day (which I'll talk about in another essay because I did eventually end up doing that).

But I didn’t meet the language requirement, so instead, I ended up in London. It was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. I had never traveled anywhere by myself. And internationally? Girl, bye. But something inside me told me I needed to go.

Picture this: I step off the plane in London, 19 years old, in a city that feels like a more buzzy, rainier New York. Big red buses, black cabs, people zooming in every direction. It’s poppin’! And there are Black people everywhere. Africans, Caribbeans, a mix of cultures and accents that felt both foreign and familiar at the same time.

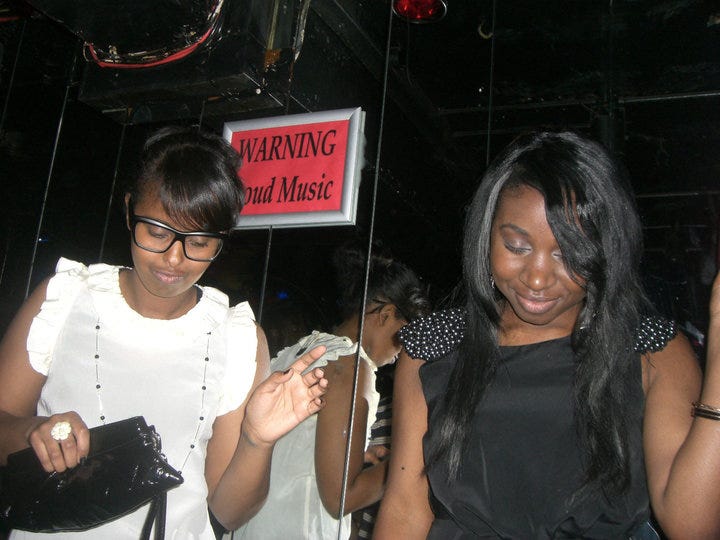

My friends and I were experiencing a lot of firsts—our first time abroad, our first time navigating a new city on our own, our first time doing things alone. If my friends didn’t want to go do something, I’d go by myself. I got invited to my first fashion show, and I also snuck into a few. I wandered through markets, museums, and ate at restaurants alone.

And then there were the men.

London's nightlife scene is crazy—Bar Rumba, Hip Hop Karaoke, Fabric. There was so much to do, and we partied until 4 am every weekend. All of a sudden, something started happening to me that had never happened to me before.

Men were looking at me. For the first time ever, men were approaching me. Not in a “hey, what’s up, bruh” type way. But as in, “You’re fine, and I want to holla at you.”

I was shook.

When you go from being completely unseen—painfully aware that you are not that girl—to suddenly being noticed everywhere you go, it’s jarring. I didn’t know how to handle it. I didn’t even know how to talk to these people. I was naive and awkward, and because I wasn’t used to this attention, I got into some situations I shouldn’t have been in. I even had a stalker at one point. But on the other side of that, my brain started to rewire itself.

Wait… y’all see me?

Y’all like me?

Y’all are talking to me?

It hit me: hmm, maybe I wasn’t ugly. Maybe I just grew up in a place where people didn’t appreciate dark-skinned Black girls. Maybe outside of California, I was attractive. I was seen.

For a 19-year-old girl who had never felt that way, that realization was everything.

Now, in my 30s, male validation doesn't mean much. But back then? It meant a lot. In hindsight, I understand that the validation I was getting in London was in some ways healing me. Within the comforts of my shell, I felt like I didn't deserve to be this outgoing, feminine, desirable woman. I knew what my looks came with: having a bigger nose, darker skin, and being African. I accepted it for what it was. We also didn't have the imagery we have today. There's so much representation online of being dark-skinned, African, and desirable that just wasn't available to me back then.

For the first time, I felt worthy. And it wasn’t just about men—it was about how I carried myself. I started taking myself out on solo dates. I went to concerts alone (I even saw Little Simz before she blew up). I took risks, explored the city, and lived my own life instead of shrinking into the background.

That trip planted a seed of confidence that grew with every solo adventure I took afterward.

And listen, I know the internet loves to shame people for seeking external validation. “Love yourself, sis.” “It all starts from within.” “No one can make you feel worthy but you.” It can start within, but for some of us, that outside validation of worthiness, attractiveness, humanness, of looking past my features and accepting me as just a woman, is actually the catalyst that starts us on that path of self-love and self-acceptance. Without it, it would have been a long time before I realized that I could find other ways to accept myself. Think about when you see a YouTube or TikTok video from a creator where it feels like they're speaking your story. Like they're speaking directly to you. Is that not validating? And is that not external validation?

Sometimes, external validation is what nudges you toward internal validation. Sometimes, that moment of being seen by the world is what makes you realize you deserve to be seen by yourself, too.

That’s what London did for me.

This is such a growing up dark skin experience—-

Wait… y’all see me?

Y’all like me?

Y’all are talking to me?

Nobody else has this experience 😭

This was so good! No wonder why you often see travel as a pivotal point in a woman’s story when retold for tv or movies. This designated so much. I’ve recently been having a pull to travel more. Im actually sitting in the passport office!! And while I’m not in “need” of outside validation I am excited for that foreign favor 😂

Awesome read, love !!